(Editor’s note: Robert Morgan passed away on July 16, 2016, at age 90. This article, originally published in the 2007 edition of Bonesville The Magazine, recounts the battles he and others waged decades ago against North Carolina’s entrenched political and news media establishments to transform East Carolina College into East Carolina University and establish a powerhouse medical school that is a strategic asset for an entire region. Please send an email to editor@bonesville.net if you would like to purchase a PDF version of the complete 2007 Bonesville The Magazine for $6.95.)

by Al Myatt

Football coaches sometimes say, “It’s not the size of the dog in the fight, but the size of the fight in the dog,” when describing the value of heart and perseverance in adverse circumstances.

“I was always too small to play any ball,” said former United States Senator Robert Morgan, who graduated from East Carolina when it was a vastly different center of higher learning.

Despite limited stature, Morgan emerged victorious from many a political dogfight, some of which were essential cornerstones in East Carolina’s progression from its origins as a training ground for teachers.

As a state legislator in the 1960’s, Morgan led the political battles that landed a medical school in Greenville. He later fought successfully for university status for the institution originally named the East Carolina Teachers Training School.

Morgan’s legislative work was vital in charting East Carolina’s present course.

What Morgan lacked in physical presence he made up for with political connections, influence and savvy. Although he stands just 5-foot-7, he was a heavyweight champion in the political arena.

Former East Carolina president Leo Jenkins and Morgan worked together at a time when powers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and its powerful allies throughout the state sought to suppress East Carolina’s aspirations to grow and rise.

Morgan reflected on the behind-the-scenes maneuvering and tactics involved in his efforts on East Carolina’s behalf from his law office in Lillington this past spring. He recalled a bitter struggle with UNC-Chapel Hill interests attempting to keep East Carolina pigeonholed in its traditional role as a small regional college.

It’s interesting that Morgan would wind up in position to win major wars against political Goliaths for East Carolina, considering the unanticipated circumstances that led to the start of his political career.

Morgan didn’t push or buy his way into politics. His first offices predated his arrival in Greenville.

“I remember I was treasurer of the eighth grade,” he said. “You didn’t ask anybody in high school to vote for you. I was president of the senior class (at Lillington High School).”

East Carolina days

Morgan followed an older sister, Ester, to East Carolina. He said his family couldn’t afford nearby Campbell. Robert and his sister were the first in their direct lineage to attend college. They were among six children born in a house north of Lillington which had no water or electricity.

Morgan said he studied under three of the original faculty members at East Carolina, who were hired at the college’s inception in 1907 – Maria Graham, Sallie Joyner Davis and Mamie Jenkins.

“That tells you how old I am,” he said.

The scene has changed dramatically since Morgan matriculated.

“East Carolina Teachers College – that’s what it was when I first went there in ‘42,” Morgan said. “There were a thousand girls and there weren’t but 50 boys. ‘Course the boys were off to war, you know.

“When we’d walk down the campus, the girls would whistle at us.

“We ate dinner at night around the family table and you were assigned a table. After that we went to Wright Auditorium where the gym was and they had a record player. We danced for an hour. The girls stood in the middle of the floor and they would break (cut in) on the boys. There was no way a boy could get off that floor.

“I wouldn’t go for a while unless my sister would be there to get me off for a rest.”

A coed from Sampson County named Katie became Morgan’s dance partner one evening and that was how he met his wife.

“Katie broke on me – jitterbugging,” he said. “We’re still jitterbugging – what? – 60-some years later.”

Entry into politics

Entry into politics

Morgan left East Carolina to serve in the Navy. He returned and graduated in 1947. He continued his education in law school on the old campus of Wake Forest.

“I never thought much really about politics,” he said.

That changed when the Clerk of Court position in Harnett County became vacant. The former clerk, Howard Godwin, was appointed a judge.

“He was from Dunn, one of the Godwins from down there,” Morgan said. “He defeated Mr. (L.M.) Chafin in ‘37 for the Clerk of Court. The Governor (Kerr Scott) appointed (Godwin) a (Superior Court) judge and that set up a vacancy in about March of ‘50.”

That vacancy led to a visit to the old Wake Forest campus by two of Harnett County’s powerbrokers of the era, Venable Baggett and Dougald McRae, who did not want to see Chafin return to the clerk’s office.

“I’d never heard of Venable Baggett,” Morgan said. “I’d never heard of Dougald McRae. Anyway, they thought the judge, (C.L.) Williams, was going to name Mr. Chafin, who they defeated in ‘37, to come back in there and they didn’t want him.

“Somebody had told them that this young man from across the (Cape Fear) river – he’s graduating from Wake Forest, his daddy was a Democrat – so they came up there and asked me to run.

“It shocked me. To be honest with you, I did not know what the Clerk of Court did. Well, Dr. (I. Beverly) Lake was my professor. He was the most revered and the most brilliant professor that ever taught there and I went in and talked to him.

“He said, ‘By all means, you go home and run. But let me warn you, you’re not going to win. But I’ll tell you what it’ll do. When you open your law office in Lillington, people at least will know who you are.’”

So Morgan did run.

“I’d come home Saturdays and Sundays and I’d travel this county,” he said. “I knocked on every door. They had me go see Judge Williams, who was the man who was going to make the temporary appointment. I went to see him in Sanford. I was just scared to death. I’d never been before a Superior Court judge and I told him that I wished he would make me the interim appointment for the job.

“He listened to me. He knew everybody was scared to death of him and when I got through, he said, ‘I’m not going to appoint you.’ You can imagine how my face flopped. Well, he said, ‘If I appointed you, you would never finish law school.’ He said, ‘You’d get elected Clerk of Court and you’d get elected two or three times. But when you got too old to do anything else somebody would come along and say, ‘A new broom sweeps clean’ and they’d sweep you out of office. Then what are you going to do?’

“So he appointed a temporary. I did run for clerk. I made him the promise that I would not serve but one term. I did finish law school – just like Judge Williams told me to do.”

Morgan won the election for Harnett County Clerk of Court and Baggett told him how he wanted him to run his office. Morgan said Baggett told him to have his desk near the front door and to meet people as they came in. Morgan would take people back to others in the office where business was conducted. The result was that people who came to the clerk’s office met Morgan as the de facto receptionist and in the process got to know him personally.

Morgan served in the clerk’s office from 1950 to 1954 – one term – good to his promise to the Superior Court judge. Then he opened a law office.

“I didn’t have any business,” he said.

His political backers had other ideas about how he could spend his time and energy.

“They said, ‘You don’t have any practice. Why don’t you run for the (state) senate?’

“I did.”

While in the state legislature, Morgan became the first alumnus to serve on the East Carolina Board of Trustees. This photo (ca. 1964) from The Buccaneer is of one of the meetings of the Board of Trustees. (Left to right): two unidentified men, Henry Oglesby, Mrs. Belk, unidentified man, Robert Morgan, Leo Jenkins, William Blount, unidentified man, Fred Bahnson, Irving Carlyle and Agnes Barrett. (ECU Archives Photo)

Establishing the medical school

Morgan served as a senator in the state legislature until 1967 when he ran successfully for state Attorney General. While in the state legislature he became the first alumnus to serve on the East Carolina Board of Trustees. He recalled that one faction in Greenville supported a particular candidate for a vacancy on the board and another group supported another man.

“Governor (Luther) Hodges was in a bind and he knew I’d gone to East Carolina,” Morgan said. “I was in the legislature. He called me and I started serving. A Dr. (John Decatur) Messick was president then and Leo Jenkins was the dean.”

When Messick resigned after 12 years in which enrollment tripled and there was significant building of facilities on campus, a motion was made that Jenkins be made president.

“I opposed it,” Morgan said. “I filibustered it for an hour or two – not against him, but I said if we pick him without a search committee, he’ll never survive it. Anyway we did have a search and Leo became that.”

Jenkins served from 1960 to 1978 as President/Chancellor of East Carolina. The title of the position changed in 1972 in connection with a restructuring of the state’s higher education system.

“He was a dynamo,” Morgan said. “Everybody liked him and he loved the East.”

When Jenkins and Morgan began working in tandem on behalf of East Carolina, it created a force that would shake the state’s traditional power structure to its foundation. The dynamic duo encountered resistance when they sought to establish a nursing school at East Carolina, a prelude to wars ahead.

When Jenkins and Morgan began working in tandem on behalf of East Carolina, it created a force that would shake the state’s traditional power structure to its foundation. The dynamic duo encountered resistance when they sought to establish a nursing school at East Carolina, a prelude to wars ahead.

“You know we’ve got one of the best nursing schools in the country,” Morgan said. “It primarily trains people now to teach nursing school, but Dr. Jenkins and I went before the Board of Higher Education – the Board of Higher Education it was then, not the Board of Governors – and a Colonel (Lennox Polk) McLendon – he was a big UNC man and everybody called him the Colonel – was Chairman.

“After we made our presentation he turned around to the Executive Director of the board and said, ‘Don’t we have a nursing school in Chapel Hill?’ He said, ‘Yes sir.’ (McLendon) said, ‘I don’t think we need another one.’ And that was all the hearing we got.

“So then (N.C. Representative and later U.S. Congressman) Walter Jones and myself introduced a bill in ‘59 to create a nursing school. But anyway, the fight began and I mean it was mean.”

In 1963, Morgan recalled that a feasibility study of a state medical school in Charlotte was quickly shot down.

“The dean of the medical school at Chapel Hill who had always fought us – we were talking about Charlotte then – but that immediately came back – and said we didn’t need another medical school,” Morgan said.

That didn’t deter Morgan from moving forward on behalf of a medical school at East Carolina.

“In ‘65 session, that’s when we introduced a bill to create a two-year medical school at East Carolina,” he said. “A Dr. (Ernest) Furgurson from Plymouth stopped by to see Dr. Jenkins one day and said, ‘We quit sending premature babies to the hospital. The nearest hospital that can treat them is at Duke and they usually die before they get there.’”

The point was that the East needed better – and closer – medical care.

“Dr. Furgurson, he was really the founder of it,” Morgan said of the medical school concept for East Carolina.”

The push for a medical school at East Carolina also got assistance from Dr. Wilburt Cornell Davison, who was the first dean of Duke’s medical school.

“Nobody ever knew this publicly – people wondered how Leo and I got so much information. It was Dr. Davison. ‘Course, he couldn’t come out publicly.

“We finally got it passed and the reason we got it passed was Dean Davison showed us statistics that there were hundreds and hundreds of vacancies in the third and fourth year medical schools across the nation. People get in medical school and they flunk out before the third year. His idea was, ‘Let’s have a good two-year school that we can feed these into these vacancies’ – and that’s what was passed. It was still a fight to get any money from the legislature.”

East Carolina was authorized to establish a health affairs division as a foundation for a medical program, and then a one-year medical school whose participants completed their medical education at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, according to the East Carolina medical school’s website. The school was named the Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University in 1999.

When Morgan toiled for East Carolina’s betterment, he often faced media opposition. Influential positions at the state’s newspapers, including editorial writers, were often held by graduates of UNC-Chapel Hill’s school of journalism. Their views were often expressions of their college loyalty.

The Washington (NC) Daily News was an exception. Its owner, editor and publisher, Ashley B. Futrell, was a Duke grad, a former Blue Devils baseball player and a champion for East Carolina’s expansion and improvement. He used that influence as a state senator and on his paper’s editorial page.

“We’d print out Ashley’s editorials and distribute them in the legislature,” Morgan said. “It was our way of balancing the media voice at the time. He sat behind me in the senate and I can still hear him saying, ‘Little Man, here’s what you need to do.’”

Once established, East Carolina’s medical school soon grew. Gerald Arnold, a law partner of Morgan’s, introduced the bill in the legislature in 1972 to make the medical school at East Carolina a four-year program.

In 1974, the legislature appropriated funds to establish a four-year medical school at East Carolina, according to the medical school website.

Since 1977, when the first class of 28 students enrolled in the four-year medical school, the institution has grown dramatically in its teaching, research and patient care roles.

Morgan said that once ECU’s medical school was approved, it received support from some of those who had opposed it or stood by the wayside while the political wars raged. Morgan noted with a degree of bemusement that Governor Jim Hunt was not active in the political battle but was eager to take credit once the medical school was established.

“To Governor Jim Hunt’s credit and Bill Friday (former head of the UNC system) – oh, Bill Friday hated me. Nah, I say hated me – the animosity was pretty strong. But once we whupped ‘em, to use a down home word – he and Jim Hunt said, ‘All right, we got it, now let’s make it the best.’

“I can’t believe in just 25 years the medical school is rated by U.S. News the ninth best medical school in the country for training primary care doctors. But it’s still going on. Everything we got down there was a fight.”

Fight for university status

Approval for the initial stages of the medical school was just a warm-up for the battle over East Carolina’s bid for university status.

“The next session of the legislature I introduced a bill to make East Carolina a university – and all of these things were Leo Jenkins,” Morgan said. “I give him credit for all of it. I was just his foot soldier.

“Leo was a major in the Marine Corps in the South Pacific. He had a picture of a head he had cut off of a Japanese. He was tough.”

Morgan said Jenkins had the picture hanging on the wall of a little hall in the president’s house.”

“We worked together,” Morgan said. “He was a good director. But we introduced the university status. We talked about the idea and we knew there was something about a university that people – academicians – you know, they’d rather teach at a university.

“Back in those days, you had Duke and North Carolina. Wake Forest was not a university. But we thought East Carolina was ready. … We introduced that bill and we passed it in the Senate, but when it came over to the House of Representatives – you know it had to pass both houses – it got killed because Governor Dan Moore was a UNC man. His blood was blue and white, you know.

“And we still had to fight Watts Hill and that crowd – Watts Hill, Jr., who was the chairman of the Board of Higher Education – the very richest people in the state. UNC people, you know – Carolina Inn and all those things. Well, we passed it in the Senate but when it got over to the House, they killed it.”

East Carolina’s bid for university status was resurrected with some valuable counsel.

“I got a telephone call one night from Terry Sanford,” Morgan said. “He’d been Governor and he was in town and he said, ‘I want you to come down here and talk to me. He was a great pro-education man.”

The issue was too controversial for Sanford to be publicly involved, but he offered his support for East Carolina behind the scenes.

Sanford was so highly respected in education that he served as president of Duke, an almost inconceivable position for a UNC-Chapel Hill graduate, prior to a term in the U.S. Senate. Sanford was reportedly John Kennedy’s choice for vice president on the 1964 Democratic ticket prior to JFK’s assassination. Morgan and Sanford served together in the North Carolina Senate.

Sanford had a plan that got East Carolina’s bid for university status back on track.

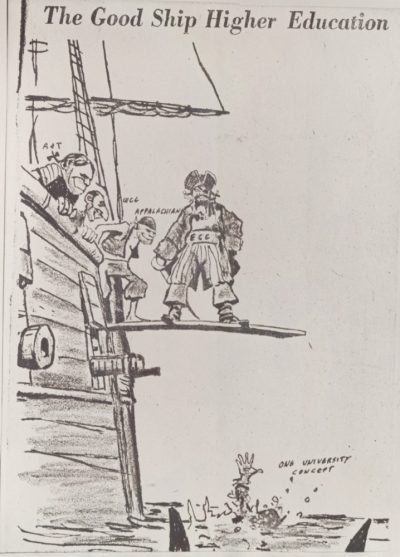

A variety of political cartoons appeared during the Leo Jenkins/Robert Morgan Battle for ECU era

“(Terry Sanford) said your problem is your base of support is not broad enough,” Morgan said. “He said the people in the Piedmont and western North Carolina really don’t have much reason to support East Carolina.

“He said, ‘I think if you introduce a bill making East Carolina, Western Carolina and Appalachian regional universities – that concept is coming whether we want it or not – you will have a broader base. The representatives from western North Carolina will be supporting you.”

At Morgan’s urging and with an eye to expanding the bill’s appeal, it was introduced in the upper chamber by Senator John T. Hensley of Cumberland County and passed.

“Every bill has to pass three readings,” Morgan said. “When you introduce it, that’s the first reading. Then they have to vote on it again – that’s the second reading. And then the third reading – you vote on it again if it passes the second. Well, we passed it over there in the Senate and then it went to the House.”

Morgan soon found out there were some powerful interests plotting against the bill’s ultimate passage.

“I came home from Raleigh one night,” he recalled. “We all stayed in the old Sir Walter Hotel and when I got back about midnight, there was a car sitting in front of the Sir Walter Hotel. There was a black lady, Dr. Helen Edmonds, who was a professor at North Carolina Central and really a renowned expert in international affairs.

“I can’t remember the black gentleman’s name, but they were two of the three people who were running North Carolina Central in the absence of a president, while they were searching for a president.”

Morgan was about to learn how devious, intense and nasty the efforts had become to suppress East Carolina’s bid to become a university.

“Dr. Edmonds said to me, she said, ‘I promised myself last night that I wouldn’t put my head on a pillow again until I told you what they’re trying to do to you. They had a meeting in the Governor’s office with Governor Moore, with Watts Hill, Jr., and the President of the university, Dr. Friday’ – (aside) we’re good friends (Morgan and Friday) now after all these years.”

“She said they had a meeting on how to defeat East Carolina’s efforts to be a university. They said to the Governor that they should send out a message to all of the black colleges – the Governor and Watts Hill, Jr., as chairman of the board of higher education to all of the black colleges – North Carolina Central, Elizabeth City State, A&T in Greensboro, etc., directing them to ask that they put the black colleges in it, too.

“See, we’d already passed it in the Senate. She went on to say, ‘At North Carolina Central, we refuse to do it because we knew they were not interested in us in improving our education. They were just interested in using us to kill East Carolina’s efforts,’ because – you know – black feeling was still pretty strong in ‘67.

“The premise was Senator Morgan will never agree to accept black institutions as part of the regional university concept and that will kill East Carolina’s efforts to be a university and it will get rid of Morgan as a politician, too.”

Morgan shared what he had been told of the plan with Jenkins.

“We decided the best thing to do was do nothing right then because we’d already passed it in the Senate,” Morgan said. “Well, the next day when it was in the House on the second reading, Jim Exum, who was the representative from Greensboro who was later Chief Justice of the (state) Supreme Court, and Mr. Phillips, who was a representative there, introduced an amendment to add A&T – the other black colleges wouldn’t do it – to the regional university concept.

“We decided the best thing to do was do nothing right then because we’d already passed it in the Senate,” Morgan said. “Well, the next day when it was in the House on the second reading, Jim Exum, who was the representative from Greensboro who was later Chief Justice of the (state) Supreme Court, and Mr. Phillips, who was a representative there, introduced an amendment to add A&T – the other black colleges wouldn’t do it – to the regional university concept.

“It was a big debate and the House adjourned about 3 o’clock.”

Morgan was waiting outside to talk with Exum.

“I said, ‘Now Jim, before we go out here to this meeting, let’s count our votes now. Let’s make sure we’ve got enough votes to pass this on the third reading tomorrow.’ He said, ‘I’m not going to vote for it tomorrow. I’m going to vote against it tomorrow.’ I said, ‘Jim.’ He said, ‘I added that because I knew you wouldn’t accept it and that’s the way to kill the bill.’

“I said, ‘Jim, you are a racist SOB.’ I don’t usually use that phrase – that’s the only time I used it that I know of. I said, ‘I knew what you were doing all the time.’ I said, ‘I had that information. You did it thinking you were going to destroy East Carolina’s bill.’ But I said, ‘Let me tell you something. A&T is going to be a university tomorrow – whether you want it or not – because we’ve got the votes to pass it.’ “

Morgan said the House passed the amended bill the following day and sent it back to the Senate to approve the addition of A&T. Morgan said the bill received final approval on July 1, 1967. Morgan said he made the only speech of his legislative career from the Senate podium, welcoming A&T to university status, along with East Carolina, because both institutions knew what it was like to deal with bias.

“That’s how mean that campaign was, but it’s really done a lot of things,” he said. “It’s enabled us to offer PhD degrees in several areas. The medical school and our athletic programs have moved up. You know, old Leo got the stadium going.”

Morgan’s efforts helped put the Pirates on more balanced footing with some of their sister programs in the UNC system. Having UNC-Chapel Hill and N.C. State come to Greenville for football games in the same season – as is scheduled in 2007 – is almost inconceivable considering the resistance ECU faced in the political wars of the 1960’s and ‘70’s.

“Getting East Carolina into the ring of playing Carolina and State was not easy,” Morgan said. “Here again, it was Leo and the coaches. I didn’t have much to do with that. Dr. Jenkins would use me when he wanted to.”

Despite his modesty, Morgan should not be characterized as anything less than a vital force in East Carolina’s transition from a teacher’s college to an institution that has reached the stage of national recognition in its continuing development.

Morgan characterizes Dr. Steve Ballard, current ECU Chancellor, as “another Leo Jenkins” – high praise indeed, which reinforces East Carolina supporters’ optimism that another quantum leap in the university’s stature will be realized during his administration.

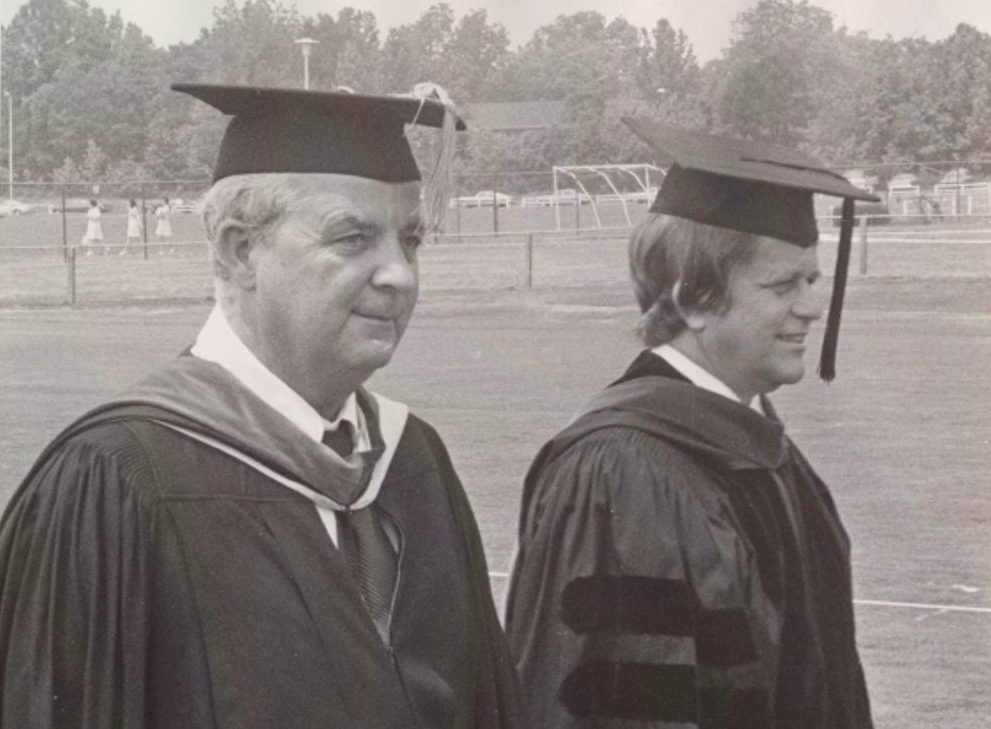

Morgan does note with a degree of pride that he and Jenkins were conferred honorary MD’s with the first four-year class produced by the ECU med school. His ECTC diploma, he said, hangs in a prominent place in his home. East Carolina has come a long way since he received his degree from ECTC. His efforts have been instrumental in that journey.

From 1975 to 1981, Morgan rose in his unforeseen political career to President Pro Tempore of the State Senate, to North Carolina Attorney General, then to U.S. Senator. In the above photo, taken during Jimmy Carter’s administration as United States President, Morgan is on board Air Force One — sitting in the President’s seat! He described the above photo thus: “We were flying across North Carolina. [The President] had been walking around the plane and I sat in his seat. When he came back in, I started to get up. He said, ‘No. I’ll sit right here.’ — on the floor. You probably will never see another picture [of] a freshman Senator in the President’s seat and the President sitting on the floor.” (Submitted)

Finally practicing law in Lillington

Morgan is the only person to receive East Carolina’s Alumnus of the Year award twice. He served on the East Carolina Board of Trustees from 1958 to 1973, the last nine years as Chairman.

Morgan bluntly states that ECU managed to survive a rocky period following Jenkins’ tenure during which the next chancellor, Thomas Brewer, operated under marching orders from Friday to undo many of the initiatives that Jenkins and Morgan had spearheaded in the 1960’s and 1970’s.

“Dr. Friday was president of the consolidated university,” Morgan said. “He appointed the chancellor (of East Carolina) and he appointed a Dr. Brewer from somewhere in Georgia who came … with the full intention of dismantling everything that Leo had done.

“If they had not gotten rid of him he would have dismantled every thing. The first thing he did was get rid of the vice president of health affairs. (The board of trustees) was able to get him fired.”

Futrell, the editor and publisher of the Washington (NC) Daily News, was chairman of the ECU board of trustees at the time and head of the search committee that would make a recommendation to Friday and the UNC system board of governors for a new ECU chancellor.

“He’s a man who saved East Carolina, too.” Morgan said of Futrell. “When Dr. Brewer was sent down here to dismantle what Leo had done, Ashley Futrell kept that board of trustees together and got rid of Dr. Brewer. If he had not, I’m sure but what Dr. Friday would have dismantled everything that we did.

“He was sort of a low key, private man but if I had to name one of the three or four people who kept East Carolina together, it would be Ashley Futrell.”

Arnold, who began practicing law with Morgan’s firm in Lillington, was from the nearby Christian Light community and was an ECU alumnus as well. He also was on the search committee for a new chancellor after Brewer resigned.

There was speculation that Morgan would be a logical candidate to carry on the work of Jenkins as ECU’s next chancellor.

“Dr. Friday told (Arnold) – see Dr. Friday would have the final say so ‘cause he was president of the overall (university system),” Morgan said. “(Dr. Friday) said, ‘You need not send Robert Morgan’s name up here because I tell you right now he’ll never be appointed.’

“I had just had the brain tumors. I didn’t want it in the first place. I never thought I was that smart. That’s when they brought (Dr. John McDade Howell), a good man. He was great big. Everybody has to be big. I wasn’t that big. (laughs)”

Morgan and Jenkins are among a handful of recipients of ECU’s prestigious Jarvis Award, named after a former North Carolina Governor from Greenville who was instrumental in East Carolina’s founding as a training ground for teachers.

Morgan himself has come full circle to the days he envisioned in law school when he planned to practice in Lillington.

He rose in his unforeseen political career to President Pro Tempore of the State Senate, to North Carolina Attorney General, to U.S. Senator from 1975 to 1981. Ironically, he was defeated for a second term in the U.S. Senate by a political science professor from East Carolina, Dr. John East, who rode the conservative coat tails of Ronald Reagan into office.

With Morgan hospitalized with a benign brain tumor during much of the campaign, East edged him by less than 0.5 percent of the vote. East, who had been crippled by polio in 1955 while serving as a Marine Corps lieutenant, took his own life during his Senate term in 1986, apparently depressed by the prospect of continuing physical deterioration.

Morgan served as Director of the State Bureau of Investigation from 1985 to 1992.

Morgan, 81, has a section of pictures in his law office that include his grandchildren. The pictures of Morgan himself are mixed, with photos ranging back to his crew cut days that show him with five former United States Presidents, including Harry Truman.

Truman was known for having a sign on his desk that read, “The buck stops here,” his acknowledgement of the ultimate accountability of the nation’s highest elected position.

Not that Morgan’s humility would permit it, but he could have a sign on his desk as well, one that would read, “East Carolina UNIVERSITY started here.”

All images courtesy of ECU Archives and the Morgan Family.

(Writer’s note: My thanks to Robert Gray, Jr., for his role in this story. His father, R.A. Gray, was a roommate of Mr. Morgan’s at ECU and later served as superintendent of the Harnett County schools. Robert Gray, Jr., arranged an interview with Mr. Morgan and provided valuable background information as a lifelong friend and admirer of the Morgan family. He also provided useful information and perceptions as a copy consultant. We were both informed and entertained by the hours that we spent with Mr. Morgan in his law office. Mr. Morgan readily conveys the qualities of warmth, humility and integrity that made him the personal friend of presidents and an effective public servant who indeed has done his alma mater proud.)

Thank you for running this again. It was great to here about the fight to bring the medical school to Greenville !! That’s the Spirit of The East and saga of a real PIRATE!

Don: I appreciate your comment. Few people younger than about 60 have a grasp of this important history about ECU’s fight to serve the region and the state. I can personally attest that the article, in its original print format and in a couple of subsequent online versions, has drawn more interest than any other story we’ve run in Bonesville’s 20-year existence. — Danny Whitford, Editor

Thank you for publishing this article again. I read it in 2007, but all of us with ECU connections need to be made aware of the efforts of so many on our behalf. My late father in law, R. Frank Everett, from Martin County, and a former State Legislator, and a WWII battlefield commissioned Marine Captain, was a good friend of Leo Jenkins. He, along with many others worked behind the scenes, to enlist support for the nursing and medical schools at ECC. Robert Morgan, also along with many others, was not limited by the height of his body, he overcame what he lacked in stature by the enormous size of his heart. He fought tirelessly along with Jenkins, Futrell, Sanford, Furgurson, and many more for what was right and just. The ECU Brody School of Medicine and the former Pitt Memorial Hospital, currently Vidant, have been a God Send to the people of Eastern North Carolina who otherwise would have to go to Duke or UNC Hospitals for major surgeries and/or other serious medical issues. I agree with Don Tyson that Morgan was a real PIRATE!